Tapped Out

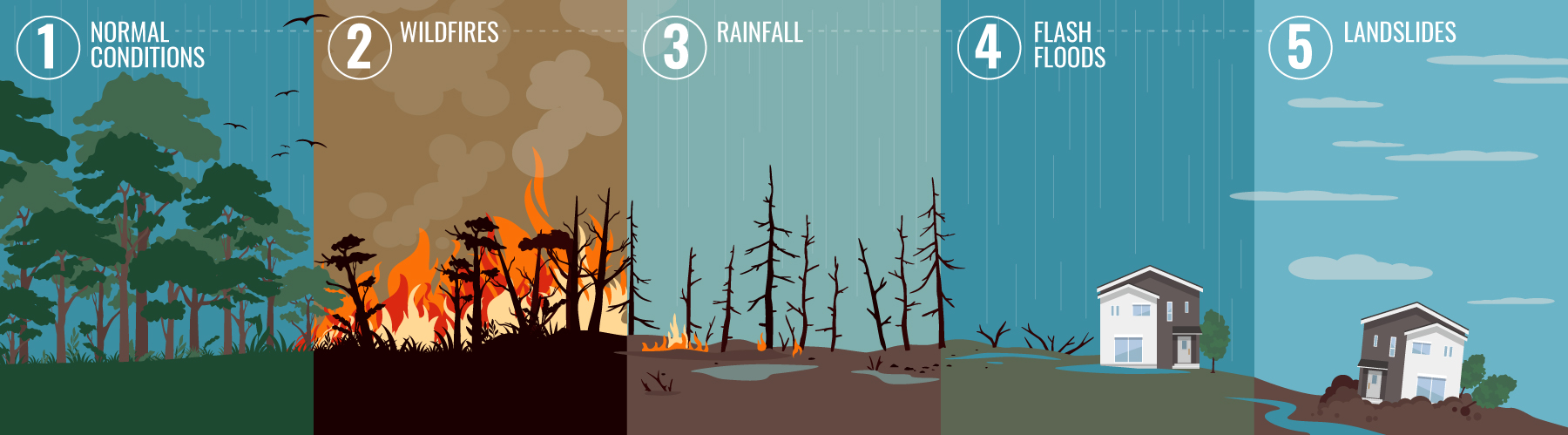

The domino effect: Drought leads to dried-out brush, which becomes fuel for wildfires. Wildfires incinerate brush that would normally absorb rainfall. As a result, during the rainy season, residential areas become flooded. Prolonged periods of flooding can lead to landslides.

“Climate change is screaming into our faces.”

–Dr. Emily Fairfax, assistant professor of environmental science and resource management, CSUCI

“Because it's getting warmer, evaporation will increase, so even if you get the same amount of rainfall, more of it's going to evaporate before it can get into a reservoir or sink into the groundwater.”

–Alison Bridger, Ph.D., San José State

“As extreme drought claims most of the state, California Governor Gavin Newsom…asked Californians to voluntarily cut their water use by 15 percent.”

–CalMatters

STORY: MICHELLE MCCARTHY

PHOTOGRAPHY: Patrick Record

Share this story